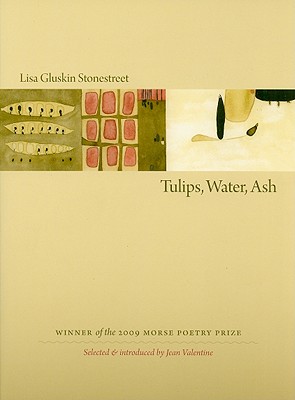

Tulips, Water, Ash by Lisa Gluskin Stonestreet Tulips, Water, Ash

|  |

Tulips, Water, Ash, Lisa Gluskin Stonestreet’s first collection and the winner of the 2009 Morse Poetry Prize, achieves the rare and difficult feat of arcing through the dull rituals of everyday life to the most profound questions about being, finding meaning in both realms. In these carefully wrought, clean poems, Stonestreet examines and illuminates both the objects of daily existence – “the mailbox, the toaster, the dentist office” – and the deepest questions a human being can posit about their existence – why am I here, and what is my place in the universe? The poem which starts the collection, “De Profundis,” beautifully sets Stonestreet’s agenda by questioning the worth and meaning of daily life – “the middle, the soft / chewy center of here” -- and calling for some experience of elsewhere, of more, of God in the midst of minutiae: “Oh, lord. Remember // us, here: the soft warm milky middle, / its erasing breath, its easy arms.”

The poems in part one present a difficult problem: how we, as human beings, long for transcendence, but are nonetheless mired in the minutiae of our lives. In “View from the Headlands,” Stonestreet provides a view of life as cluttered by necessarily rote. Human beings are, essentially, trapped; the possibility of transcendence has been ruined by the stale steps one must take every day for survival: “The longer I know it, my husband says, this place, / the worse I know it is—the ruined, // the once.” The poem ends, however, on a note of hope: Stonestreet sees that “[t]he moon hung, or was tethered, low in its cradle,” thereby questioning whether this is an actual trap or merely a trick of perception.

Stonestreet picks up this theme again in “Jars,” in which she presents the possibility that even in — or by — our daily lives, we can be transformed, but that we are resistant to this: “What did I think / would happen? We were transformed, / and obstinate.” In “Potential,” Stonestreet relates this to the difficulty of escaping routine, or, rather, perceiving the routine in another way: “No getting away from the world, at least for now: even on the good days / it’s wash and backwash [...] Each discarded bottle an egg dream, a push to the next / and next.” Even the smallest and most seemingly useless object, then, contains within it the potential for transformation, like an egg contains its yolk; however, we merely discard and push things away.

Stonestreet suggests, in “Painting the Existent,” that this is due to the brute human tendency to believe that the other is better, the “there so compelling” — that only through escape will we seek release, salvation from ourselves, or what we have made of ourselves. Perception, then, is the essence of the problem, as Stonestreet’s “Thought Experiment” suggests:

See:

Yesterday you met me at the train. Next year

is a leap year. All our present

spent elsewhere, a mirror held over the shoulder

and a smaller one, fogged, close to the eye.

The following poems tackle the parts of life which should allow for some kind of transcendence: sexuality, the power to join two being into one, and reproduction, the power to create another human being. Here, Stonestreet again posits the possibility that perception is the problem, that, through being caught up in the dailiness of life, we see even these aspects of human existence as routine. In “Married Sex,” Stonestreet meditates on what sex could be:

that lostness

you’d once do anything for:

to be made

nothing again, perfect

not-being —

Sexuality has the potential to take us outside of ourselves and create a moment of “perfection;” however, by making sexuality routine, we drastically change our perception: “Now you are something else: / not not [...] / Flush all the time / with the seeing.” What we see, however, removes the possibility of release. Even the power to create new life is reduced, not glorified as it once was in the body of Persephone, who, in “Persephone at 13,”

can swim in and through,

tail flicking, down into the earth

of her own flesh, becoming in her descent

a cell, an electron, small thing spinning

in a great void.

In the classroom, Stonestreet learns of her body and its great capacities through watching fish which the teacher presents as expendable, as nothings, “Dime a dozen, those depths, those five / red jewels. All the girls are doing it. Dark matter / richer than loam, its loping song— pull of away, of in.” As these lines suggest, there is still the promise of transcendence, if only through the desire for extremity, a moment to jog one from routine, as “Catapult” illustrates:

[...] Nights

we tried for momentum, some catapult

of desire that could lift us out of one life

and into the next [...][...] Plotted escape from something

not so bad, that is, intolerable.

The poems which follow offer a kind of wistful hope by working through the problems of perception. In “From Then,” Stonestreet suggests that alternate ways of perceiving the world — through, for instance, poetry — can offer a path to release, however limited it may be. Poetry, here, acts as divine inspiration, a ladder up which — or down which — one can escape from the routine of “dirty linoleum. One shoe squeaking / against the other.” Poetry becomes the intersection of the divine and the ordinary, through which Stonestreet “held the pearl. I slipped back down / through a hole in the net.” This is because the person — the self — is not entirely present in the moment of creation; rather, poetry comes through the person,

who must in some sense become other than their self. “We’re used / by sweetness—” suggests a solution in blankness, a moment when the self is not so concerned with the self and transcends the limits of daily, earthly life:

Use me then, take me

humming and buzzing

down into

hallelujah blankness—

[...] that one

moment of sweet forgiving

nothing-elseness. That thing

we’re made for.

In part II, Stonestreet moves from seeking a solution in the self and the body to examining the very laws of space itself: its elements and its particles, its universes, all tending to the left, the right, the irregular, and the strange, as do human beings. In “Dark Matter,” Stonestreet explores the great mystery of what cannot be seen, seeking a definition and therefore, perhaps, a solution, as though, by naming, she can lay claim to the mystery and therefore gain a sense of agency and control over it: “It is only the space between stars.” Stonestreet links the laws of the universe at large with the laws of men:

—everything now is farther but gets there

faster: light in the wires, your hand

as it lifts toward your face, more distant

by an atom than the day before.

“The Anthropic Principle” turns again to the idea of perception, borrowing a cosmological principle circling around the fact that human are rational, and therefore any other universe that humans, or rational beings, could occupy must be a universe like this one:

The cosmologist says, We hope that we don’t have to resort to this solution.

The cheat, the lie, the truth: Orion, for example, is there

because you are there to see it.But it is one way out.

The way out, in other words, is through granting perception the ultimate power by believing that the very universe exists because we name it into existence. The human being, therefore, is of essential importance, and this transcends not only beyond the dailiness of our everyday life, but the boundaries of earth and earthly life in general:

You are there, and how long

you have not been there, how long it has been leading

up to this (mismatched and

unreal though it is, though it

will be still)— Open your view.

Open. Flooding in like stars,

everything, with its hands and its eyes.

In “Double Helix,” Stonestreet turns again to the human realm and suggests that this kind of naming, this kind of communion, is as natural to human beings as our very bodies themselves, as our very bodies function in such a manner:

Vitreous humor, spleen, all thumbs and your hand

spirals down toward completion, stripped-downtelegraph times two carrying the news of the day

and all is catch and fall, rise and carry —

Our organs work in this rhythm to catch sensory experience, and the human mind works along to carry it. We are made, then, of perception, which is itself transcendence. In “Super Baby Jumbo Prawn,” Stonestreet makes clear that the beauty of life is in the moments when we don’t seek extremity, in those quiet moment in which we can sit back and simply see: “Some days it’s enough, / sitting in the car eating lunch, / watching surfers tempt the waves.”

We are our perceptions, and we are our memories, and thus we are also our inconstant existences, our routines and our routine miseries; we are “all the buckets, dug out / by their contents, made / of their burdens.” Therefore, it is through our tragedies and our inconsistencies – both small and large, common and grand – that we find possibility, that we gain the ability to reflect back, be illuminated, shine, as in “Alluvial:” “Here, now: the compound, the rough. Something mars / the surface, lets itself in.” The important thing, recognized both by the poets and scientists, is that one changes by letting this illumination into one’s life, as in “Light as the Only Constant in the Universe:”

What is illuminated is what

is reflective, even

a little bit—roughed-up

enough to grab onto, sendsomething back.

In “Etymology of Lost,” the book’s final poem, Stonestreet turns to tragedy: “And now here I’m supposed / to detail something even worse [...] /Body in the water, pins on a map.” After great tragedy, perception alters, and it is exactly the small, routine things which matter, and which give us most the ability to be illuminated, and therefore luminous: “And then we went out for kung pao tofu, and home to bed, / and I kissed my son on his head and sang to him, // first the song about the angels and then the one about the sky.”

Reviewed by Emma Bolden.

Poets’ Quarterly | October 2009.