Issue 2 - Winter 2010 Reviews Anxious Music Blood Dazzler Cities of Flesh and the Dead Crazy Love Cures and Poisons Dark Card and Mom's Canoe Fire Pond How to Live on Bread and Music Mister Skylight Paternity Perpetual Care Pictures in the Firestorm Rhapsody of the Naked Immigrants Rock Vein Sky Six Lips Slaves to Do These Things Slide Shows The Air around the Butterfly The Guilt Gene the nested object Interviews

|

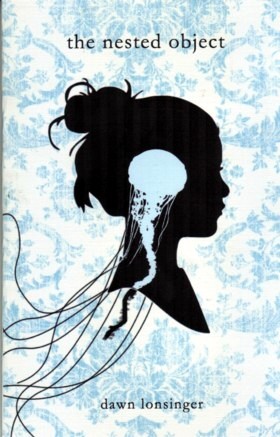

The poems in dawn lonsinger’s chapbook the nested object inhabit a physical world. They wouldn’t be out of place beneath the sea, in a forest, some place plentiful with amorphous jellyfish or moss. Poem after poem is rooted in the organic; we watch sea urchins breed, peer into birds’ nests and cling to the roots of trees. This is elemental, more so than what usually passes for nature poetry. We are not in Wordsworth’s territory either, where each encounter with nature incites reflection and transcendence. Instead, “this is where shape incubates” (“the nested object”). Whitman or Thoreau would be more at home in these poems and both are, in fact, used as epigraph for “A Wreck of Nerves // & Birdlime,” and “And Thus the Darkness Bears,” for here the body—our bodies—are just as much a part of the natural world as fire, gourds, the moon. Lonsinger is interested in the spaces between things, the wild element in each of us. In these poems, even a familiar children’s game is painted in a new light, so that it becomes beautiful and strange: “fingers generally progress toward an emerging form, the space between them nets—children open the door of the church and see all the people of their palms writhing, each one longing to lift up off the body like a balloon, a message inside for anyone with warm blood—which of us smells the designs of our skin?” (“A Wreck of Nerves // & Birdlime”) There is an ethereal quality to these words, but not in a sense that the reader is excluded from knowledge the poem withholds. We are in familiar, aqueous territory, floating, feeling “the intricate rug of ocean that is / your heart, immense serenity & torrent vast” (“Love litagates like this”). This poem begins with a chant: “sugar sugar sugar go go / go sheet sheet sheet,” questioning why we can’t feel the blood moving through our arteries, “the perpetual / massage of living.” There is an absurdist quality to some of the images, like a painting where clock faces melt, but the natural settings root us firmly, never allowing the poems to cross into the territory of ridiculous. Variety exists here, too, for alongside love poems to nature are an “Ode to Tupperware,” the “refuge / for things with a penchant for decline,” students traverse sidewalks on a university quad (“is there anything left in the leaves to speak of”), and household pets, where a Maine Coon rests atop a refrigerator (“Pet”). At first, when beginning to read this book, I felt like Alice in Wonderland, entering a foreign world, but by the end, I knew I was somewhere familiar; though everything felt still refracted, slanted, seen in a new light, a reflection of what I am used to. Lonsinger uses words this way. We recognize their meanings, but bundled together, they form something altogether new. In a letter to autumn from the poem “is there anything left in the leaves to speak of” the final line accurately describes what any avid poetry lover seeks from a new encounter with the text: “For me, I only ask that my face, like the expression of trees, is blown apart a bit by the wind.” This book delivers on that request. Reviewed by Valerie Wetlaufer. |