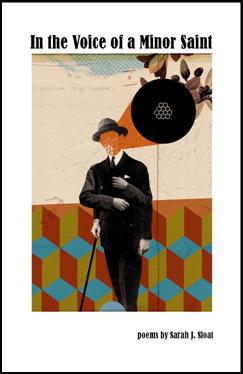

Issue 3 - Spring 2010 Reviews American Fractal American Prophet Contents of a Mermaid's Purse Easy Marks Entrepôt Flinch of Song I Have to Go Back to 1994 and Kill a Girl In the Voice of a Minor Saint Sarah J. Sloat No Boundaries: Prose Poems by 24 American Poets Noose and Hook Please Self-Portrait with Crayon Some Weather The Best Canadian Poetry The Ravenous Audience Underlife Voices Interviews

|

Sarah J. Sloat’s new chapbook, In the Voice of a Minor Saint, is one of those books that, while reading, I keep putting down. Not because it’s awful—on the contrary—I keep putting it down because it is so good. With every turn of the page, inspiration strikes. With each first line (she writes killer first lines, by the way… just try to ignore a poem that begins, “God have pity on the smell of gasoline…”), my mind reels and my muse screams, That gives me an idea! Write this down, immediately!

First line, first poem, and immediately we know, as the title indicates, we are being handed an “Opportunity” to listen up. This is our first impression of the collection’s narrator—an astute recorder of the minutest detail; a skilled observer, refreshingly unafraid of her own truths. While she claims to be “so busy/ making myself marvelous,” it is exactly in the radio’s wavering “between stations” that the poem is discovered. This is precisely where the greatest poems are written. Indeed, Sarah J. Sloat (even her name is fun to say) knows all the best places to find poems. Consider for yourself, mining a poem in “Bird-wrought dawn” or in the “Riot of rustle of sheets” (“Pursuit”). Perhaps “wallowing/ off in the wheat of long siestas” is more your speed, or “trundling down/ the loving sidewalk of lawns” (“Humidity”). Better yet, follow the lead of the narrator’s tongue in “The Silent Treatment.” Plunge “in a tunnel to the underworld where/ they stump in a strange dialect.” There is sure to be poetry lurking there. So try it. “Make pretty/ like a lake today: hold yourself in.” As if leading us on a poetic adventure isn’t enough, Sloat also provides musical accompaniment. There’s onomatopoeia, those clever words imitating the sounds they suggest, as in the aforementioned “Pursuit,” “Riot of rustle of sheets, rest sweet,” and in “Vestment,” where the narrator plans to “dress in a vest of bees” (can you hear the buzzing as she slips inside?). There’s assonance and consonance, that steady stream of surprising rhyme, as evidenced in the lovely “Ghazal with Heavenly Bodies”:

As a side note, in a recent conversation about first lines, Sloat remarked, “Funny enough, the bite-marked moon was a line nursed for ages and I could never execute a poem with it, until it found its way into that ghazal.” Getting back to the music, there is also harmony in nearly the entirety of “Europa”:

Like “the whole machine/ gas has to carry,” Sloat’s words are “lead, flesh and metals/ that do not travel light.” Yet, there is no need for pity on Sloat’s poetry machine—it runs like a dream. Clever poet, Sloat borrows from a host (sixteen, to be exact) of French poets, (mostly) surrealists such as Andre Breton, Jacques Prevert, and Paul Eluard, among others, to piece together the haunting “Naked, Come Shivering.” “Not wanting anything to die of hunger,/ the whole town has come into my room…” the poem begins, and we, readers, enter in as well, not wanting any poem of Sloat’s to perish from going unread. “Sit down, Calamity,” the poem closes, “wheat of the things of the world,” and we let go our collective breath. The dream is still beautiful. Like her surrealist forefathers, Sloat has woven a mystical tapestry from fragments. Not convinced that Minor Saint is the real deal? A major voice in a minor (if you can really call twenty-two compelling poems minor) package? Flip to page fifteen and prepare to be wooed in six lines:

As with most of Sloat’s poems, its first lines immediately engage the reader. More importantly, the poem succeeds in capturing the fleeting thought (inspiration)one might have when encountering the anomaly of a man writing a single name on a grain of rice. Captures the thought, then distills it into the simplest form, and, in homage to Samuel Coleridge, turns that thought into poetry using the best words in the best order. And then, the greatest thrill, the reader’s heady pay-off: Sloat ends the poem with a zinger, a closing that surprises and inspires, leaves us thinking, leaving us desiring more. And, yes. I left off those last two lines. Buy the book. Discover the truth for yourself. Discussing the rise in popularity of chapbooks, Jean Hartig, poet and assistant editor of Poets & Writers Magazine, noted in a recent P&W article, “the relevance of the little book is more evident than ever.” Without doubt, Sloat’s debut collection, small only in terms of the number of poems it contains, is one of the most relevant, engaging volumes I have had the pleasure of reading lately. Sadly, as with all great pleasures, the end eventually arrives. So it is with this lovely chapbook. Oh, but what an end!

“We admire devout attention to the line, focused metaphors, complexity and simplicity,” reads Tilt Press’s mission statement, adding “lyrical but not formal, dry humor, the letter y, fresh turns of phrase, slightly experimental, modern confessional…” Sarah J. Sloat’s In the Voice of a Minor Saint has all that and more. Lucky for us, though the heart of the title poem’s minor saint “is small, like a love/ of buttons or black pepper,” this slim volume is “so busy/ making [itself] marvelous” (“Opportunity”), it is “whistling like happiness itself” (“Pursuit”). Dear Sarah J., “keep it up buddy/ I follow.” Reviewed by Jill Crammond Wickham. |