Issue 4 - Winter 2011 Reviews Arranging the Blaze Beasts and Violins Crazy Jane Eating Fruit Out of Season Five Kingdoms Hard Rain Heathen Little Oceans Multiverse Open Slowly Psyche's Weathers Silent Music Something Must Happen The Apocalypse Tapestries The Darkened Temple The Kingdom of Possibilities The Tyranny of Milk This Pagan Heaven Woman on a Shaky Bridge You Know Who You Are Interviews

|

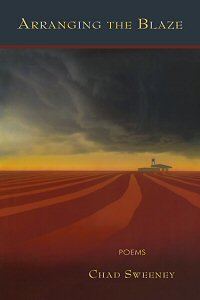

In his essay “The Language Habitat: An Ecopoetry Manifesto,” James Englehart describes and defines ecopoetry as “a way to engage the world by and through language,” and through language, the poet learns that one is both intimately connected to and, at the same time, disconnected from the rest of the world. Englehart argues that human beings share with bees the natural ability and instinct to build; however, unlike bees, “we are aware of the hives we build, why we built them, how they connect, intellectually, to other hives, other people. Also unlike the bee, when we look to other creatures, we understand that we cannot know them.” Through language, therefore, we approach the entire ecology. We learn how like we are to other creatures and creations while simultaneously learning that we are so different from other creatures and our habitat that we can never learn them, never know them. Through language, then, “the differences swirl back up to surround us and the search for poetry begins again,” and in Chad Sweeney’s second full-length collection, Arranging the Blaze, it is these differences which flame again and again, rising and falling only to rise again. Through shifting and incendiary blazes of language, Sweeney approaches and attempts an understanding of the natural world through words. In these poems, Sweeney turns his talents as a translator from others’ words in other languages to translating the natural world into language. In the process, Sweeney explores nature’s processes, discovering and discussing how they relate – or do not relate – to human beings, and how human beings relate – or do not relate – to the natural world. Perception becomes a performative act, an act of creation in which a human being realizes and creates a world – whether or not that world is the real and actual world. The questions Sweeney raises are not, however, related solely to linguistics and definition, but also to responsibility: if we realize we are affected by nature, must we also realize our effect on nature? And, if so, what is our responsibility to the natural world? Sweeney sets these themes ablaze in the proem which begins the book, “The River,” in which he begins as so many poets have begun before: by stepping out into the world to find what is there to be found – or, in the speaker’s case, to see what there is to be seen. Immediately, the reader is immersed in a world of perception and translation, in the blaze of the speaker’s mind as he watches, interprets, and attempts to verbalize and therefore understand his relationship with the world. The poem swirls around the speaker’s visiting and revisiting the river, a subject reflected structurally through Sweeney’s use of anaphora. Each return to the phrase “I went to the river” is a redefinition, and the speaker works to translate the images he sees into meaning and into some meaningful relationship between himself and the natural world. This translation into human language is necessary because, as the speaker finds on his first venture to the river, nature does not speak, or, at least, does not speak in a language he can understand: “I went to the river and watched a house burning / noiselessly, cattle birds // remained asleep on the roof.” Even in the midst of an event which surely translates as calamity and disaster for the human beings involved, nature and animals in nature keep their silence. The speaker continues to show how humans are affected by nature: “I went to the river and the wind shook me.” However, nature is not affected by his presence, or by the aspects of nature which affect him: “but did not shake the pears / from the branches.” As the poem progresses, nature becomes, for the speaker, indiscriminate and uncaring, indiscriminately destroying even those creations most revered and treasured by humans, symbols of literature and religion:

There is, of course, no one in the water, but the speaker must imagine this to be so in order to understand or deal with what he is witnessing: he must translate this indifferent image of nature into an image in which nature, in some way, appreciates the acts and works of man. As the collection progresses, Sweeney ignites and fans these ideas, recording what happens as language and perception consume and transmute the world. Sweeney opens the first section with “White,” a poem which begins by asserting the difficulty of definition:

Just as nature changes continually, so must our perceptions of nature change, and so, therefore, the language we use to describe and define nature. As the collection progresses, so does Sweeney’s ongoing process of translation. The images in each poem shift and transform as does the speaker’s perceptions. Nothing is solid, nothing easily defined. In “Genealogy,” for instance, the speaker cannot even say for certain what is within and what is without him. In the first stanza, the speaker sees “amber points of sun” “along the streets”; by the second stanza, he realizes that this light is “reflected”, and its origin, presumably, “is in me.” The boundaries between the self and the world are porous, a problem with origins in perception itself. Sweeney describes how

Here, Sweeney shows that the world itself is portraiture: every image is both painted by and perceived by a self; therefore, the world is a world in which strict and stringent definition is impossible, and language must shift in order to describe. The speaker asks “Is it jade? Is it flint? / Did waves grind it / in a mill?” The answer is that there is no answer. Definition shifts as perception shifts. There is no external and objective truth; rather, “[i]t is in me.” This idea again ignites in the title poem as the speaker arranges the blazes of light which pass through his eyes:

These fragmented images gather and accrete until the speaker connects them, and connects meaning to them: the irreconcilable shards of light soon become “gables and doors,” then “impressions of pedestrians stooped / through rain”, then “the blur of / the water tower over roof peaks in muted triangles.” Here, Sweeney shows us that the world is not a world but an artifice, a creation: we perceive fragments and we arrange them through assigning them meaning – making “triangles,” for instance, into “roof peaks” – and create the world through that perception. Through language, we simultaneously know the world intimately -- as we, in a sense, create it -- and can never know the world, as it shifts as each person looks at it, each time they look at it. Through this process, we also come to know ourselves and how we relate to others. In “Genealogy,” the speaker continues to speak of his father’s vision of wheat, “which by its very shape / reflected millennia / of locust.” Nature holds history by nature of being itself, existing to be perceived even as those who perceive it live and die. In nature, we learn not only of ourselves but of others. In looking into the world, “[b]y memory or dream” we come to see not only ourselves but our kind, from the first who described and therefore, in some sense, created the world, “the first hand to blend / pollen and clay against the cave wall.” Language, then, becomes incredibly important. In “Moving,” Sweeney writes that “[w]ords are everything / we own,” a statement which can be read in two equally significant ways. In one sense, language is really the only thing that we have, as the world we know is only a world of our own perceptions, our own descriptions, or the perceptions and descriptions given to us by others. On the other hand, everything that we think we have is what it is only because we use words to identify it, to attach value to it, and to name it. This doubled truth links us not only to the world but to the linguistic world of naming, of language and meaning, and in “Translation,” Sweeney shows how this truth can accrete great power through the examples of Palestine and Israel, for whom the poem is written. The speaker’s body becomes so linked to the landscape, so tied to this connection, that limb and land are linguistically identical. The speaker’s teeth become “the glass // of fall houses;” his body as a whole is translated in terms of the surrounding landscape, and the landscape itself is translated in terms of religious and political meaning. The wind is not merely wind but generative force, and a force which generates meaning as it “looses the doors from their moorings // and carves in the olive grove / a boy, a violin without strings.” The landscape is unavoidably altered by what occurred on, in, and around it, as are the citizens. The world is a world of perceptions and perceived meaning, but the world has meaning only because we give it meaning through a process of translation which is both natural and essential. This endless shifting of matter and meaning does not, however, release human beings from a relationship with nature, or from responsibility; on the contrary, it increases it. “The Witness” begins with the speaker awaiting the dawn of day and of his responsibility. Because of the mere nature of human perception, the speaker is called to bear witness, to create and re-create the world: “Who else but me to say it?” The speaker – and, by implication, all of us – is called to order the world, and to therefore give it meaning. In being called to bear witness, we are also called to assign meaning, and therefore carry great responsibility, like the speaker, who is “terrified // by how much I love.” Here, Sweeney takes Englehart’s theory further, positing that through perception we do not merely recognize our connections with nature, but create them. In order to fulfill our responsibility, we must create these connections with all of nature, and all things in nature,

Sweeney uses Martin Buber’s terminology to stress the point that the power of perception belongs not only to human beings, but to all creatures who perceive, and that all that exists in nature – from kelp to rats to ourselves -- has equal meaning due to its very existence. We are built to build our world in language, and in doing so, we create connections between all things which surround us. Thus, even the most humble creature is meaningful, and therefore important, “the kingdom of the small / overwhelming the kingdom of the large,” the kingdom which is able to recognize meaning and therefore is responsible for protecting it. Reviewed by Emma Bolden. |