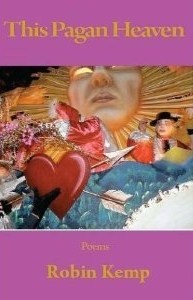

Issue 4 - Winter 2011 Reviews Arranging the Blaze Beasts and Violins Crazy Jane Eating Fruit Out of Season Five Kingdoms Hard Rain Heathen Little Oceans Multiverse Open Slowly Psyche's Weathers Silent Music Something Must Happen The Apocalypse Tapestries The Darkened Temple The Kingdom of Possibilities The Tyranny of Milk This Pagan Heaven Woman on a Shaky Bridge You Know Who You Are Interviews

|

What does it mean to “write like a girl”? While this may not be the underlying theme of Robin Kemp’s poetry collection, she does raise the question (in “The Lady Poets’ Auxiliary”) near the end of the book; and the placement of the piece suggests the reader may want to re-examine the preceding poems after having considered the implications of this sly ars poetica. But it is already clear that Kemp does not offer “ladylike” poems or sensibilities. Her work is often barbed; romance is neither easy nor always desirable, she doesn’t shy away from toughness, slang, or scientific reason. Maybe she isn’t writing “like a girl”—if we could define what that means—but she is clearly writing to be heard. Kemp employs formal strategies frequently and appropriately, possessing a deft hand with the contemporary sound of the sonnet which she uses to good effect in lyric love poems such as “Courting the Lion,” “What I Wanted to Tell You,” “Moving the Rose” and “Valentine.” But she also uses form in current-events or politically-charged poems, where the structure and limitations of the sonnet, pantoum, etc. help to point out irony, even sarcasm, in poems such as “Pantoum for Ari Fleischer” and “Editing Katrina.” These message pieces worked better for this particular reader than the looser, largely iambic free verse approach of “A Fitting Memorial,” perhaps because the formality heightens the off-kilter sense of newsfeed immediacy. That off-kilter sense works well in This Pagan Heaven, and Kemp knows how to use classical allusions and classic forms to intensify rather than balance the tensions in the topics she explores. In her world, Irony and Rhetoric are “bad girls in black T-shirts/who slouch and smoke under the spiral fire escape” while their foil, “Mr. Loner,” represents reason and logic as the quintessential nerd “positing formulaic dead-ends, prostrate only before Zero.” She riffs on Shakespeare’s sonnet 116 while bemoaning doublespeak in the well-realized long poem “Bodies” by illustrating the nuances of pitch in spoken words and adding “let us not to the marriage of double meanings.” Her approach to the usual iambic pentameter of the classic sonnet in English is sometimes to sever the reader’s expectations of language without actually dropping the metrical regularity; in lines 11-13 of a poem about rock climbing:

Here, two rather playful yet frightening lines mess around with internal rhyme, alliteration, and one-syllable words in a Hopkins-esque fashion; but there is no complicated sprung rhythm here, and lines 11 and 12 are as regularly iambic pentameter as the more recognizable 13th line. In the collection’s other ars poetica poem, “Articulation,” Kemp’s speaker observes “not everything can be explained or wrought/by reason’s cold instrument…” and suggests that composing a poem is an act of faith. The nay-saying dictatorial voice of “The Lady Poets’ Auxiliary” would not agree; but by the time the reader reaches this poem, the anti-authoritarian, skeptical intelligence evident in Kemp’s work urges a reconsideration of the roles of girl and poet and citizen. I have one disappointment in This Pagan Heaven: the absence of a poem mentioned on the Acknowledgments page, “Cento Farming.” If it was cut from the manuscript, why tantalize me with the possibility of a poem comprised of borrowed lines from Marilyn Hacker, Elizabeth Bishop, Molly Peacock, Marilyn Taylor and others? Given Robin Kemp’s facility with other forms, I would very much have enjoyed reading what she can do with the cento! Reviewed by Ann E. Michael. |