Issue 2 - Winter 2010 Reviews Anxious Music Blood Dazzler Cities of Flesh and the Dead Crazy Love Cures and Poisons Dark Card and Mom's Canoe Fire Pond How to Live on Bread and Music Mister Skylight Paternity Perpetual Care Pictures in the Firestorm Rhapsody of the Naked Immigrants Rock Vein Sky Six Lips Slaves to Do These Things Slide Shows The Air around the Butterfly The Guilt Gene the nested object Interviews

|

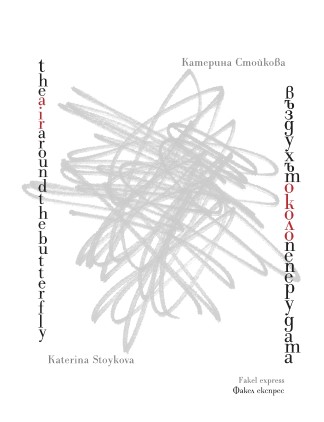

When Bulgarian poet Katerina Stoykova’s The Air around the Butterfly appeared in my mailbox, I stood at my kitchen counter and began to read. I was intrigued by the unusual cover: the paper’s rough texture, the bold, chaotic scribble overrunning the boundaries defined by the Bulgarian and English titles, the lovely shapes of Cyrillic letters. My intention was to skim a few poems and get a sense of the book before going about my day. I read the first poem and then the second. And then the third. Before I knew it, I had read the entire collection, forearms still pressed against the counter’s tile. An obvious—but simplistic—comparison is to Valzhyna Mort’s Factory of Tears. Like Mort, the English and Cyrillic texts appear side by side on the page. But unlike Mort, whose original Belarusian poems were translated into English, Stoykova wrote in English and then translated her own work. Where Mort’s poetry shouts from the page, her metaphors bold and angry, Stoykova takes a quieter approach. Her work is stark – minimalist. The poem from which the collection’s title is taken, “How to Write a Poem,” reads simply:

This is also a lesson in reading her poetry. The power of her words hovers not in the lines themselves but in the air around them. There is a clear fairy tale quality to Stoykova’s writing. Her language is narrative, deceptively simple. Take “Often I wish I Were,” the poem that begins the collection:

The first two stanzas posses a playful quality with their anthropomorphism of the potato, but even so, the reader senses a set up. And then comes the last stanza, blowing the poem apart, embedding inside it, “the difference between life and death.” Stoykova grew up in communist Bulgaria, a country where freedom of speech was strictly prohibited. In order to circumvent the threat of censorship – or perhaps worse, writers were forced to package their message inside seemingly harmless language. Often this took the form of allegory. (I credit poet Pam Uschuk for pointing me in this direction with Stoykova’s work.) Although Stoykova wrote the poems in this collection when she had the luxury of free speech, her style clearly grows from times when this was not the case. When I asked her how much she felt her history influenced her style, she replied, “The quick answer is 10 percent. The longer answer is that I think there is an influence, but it is indirect . . . when I was growing up and learning about poetry, many of the poets I read and learned from used metaphors and allegories to express themselves in safer ways.” The collection is arranged as a narrative chronology in three sections, a sort of story-in-poems of Stoykova’s life. The first section, “my mother was going to war,” draws from Stoykova’s childhood. There are poems of war, of loss and being lost, poems of a mother’s battle with cancer, all seen through the eye of a child. They are often allegorical, and often she packs an incendiary device into the ending. In “Photo of Grandpa as a Young Guerilla,” she begins:

Except for the rifle, it appears innocent enough. But then we have the last stanza:

The reader is left with a chilling simile of weapons as food and the unsettling image of these grenades/bread rolls stretched between her grandfather’s sheathed knives. In the poem “Stones,” Stoykova tackles the subject of indifference to brutality as seen through a child’s eye. She begins with a confession. “Yes/I hid/in the bush . . and we did/throw stones/at the donkey/ . . .yes/I saw/it was tied with a rope/when it tried to run”. She explains, “and I did feel pity,” but then justifies her actions with, “but they told me/it kicked people.” She ends with a damning shoulder shrug of exoneration, “but I couldn’t toss/very strong/so I don’t think/my stones hit it.” She echoes this theme again in the poem, “The World Was Starving,” which appears in the third section, “the apple who wanted to become a pinecone.” The poem is two lines:

Beyond this confession, what else is there to say? The second section of poems, “e.t. and I phone home,” chronicles Stoykova’s experience of immigrating to America. The first poem, “Plea,” deals with her feelings of starting over. Looking at her new self in the mirror she says:

The language is sparse, the beat heavy and sonorous. And as in so many of her poems, there is the last image, snow-white-innocence, that reverberate with deeper layers of meaning. She expands on her feelings in the aptly titled poem “Cold”:

The poem "Sus-toss" is Stoykova’s most confessional. Sus-toss, a Hopi word, “is the disease that causes different parts of you to live in different places.” It is dark, heavy, filled with a driving repetition that reinforces the desperation of an immigrant torn from her roots. It ends with a prose poem stanza: It feels as though you’ve moved in with your father’s new wife and now you are getting used to her cooking. . .You are noticing that she does not save the best slice of watermelon for you, and that you need to eat quickly from the dish, along with everybody else. When I asked Stoykova what she meant, she replied, “the analogy is between the birth mother and one's native country. The second wife is the new place that one must become accustomed to.” The last section of poems, “the apple who wanted to become a pinecone,” is the most playful and the most innovative. It is filled with humorous allegory, but her playful winks belie a deeper sadness:

In her poem “Tree,” she gives a wink to Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Petit Prince:

And then there is her Set-Theory-as-Poem, “Function,” that lays out her dreams and the constraints on her life as two mathematical sets, identical but rearranged:

She concludes, “She had a dream of X/It failed because of Y.” The multiple layers of meaning in the title make it both playful and damning. It can be interpreted in a purely mathematical sense, or it could mean what Stoykova must do daily to survive. The collection ends with the poem “The Apple Who Wanted to Become a Pinecone,” written as an interview between the poet and the apple. The poet wants to know why the apple has come to this decision, and how it plans to, “go about turning into a pinecone.” In the last line, the apple states, “And I will fall far, far from the tree.” Indeed, Katerina Stoykova has accomplished this with her delightfully innovative first collection. Indeed, each poem sets the air around the butterflies humming.

Reviewed by Naomi Benaron. |