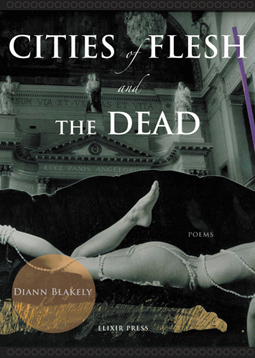

One does not simply read a new book by Diann Blakely: one experiences it. Blakely’s long-awaited latest collection, Cities of Flesh and the Dead, which won the Poetry Society of America’s prestigious Alice Fay diCastagnola Award, is no exception. In this collection, Blakely follows in the footsteps of such poets as Matsuo Bashō and Walt Whitman, treating the journey as a physical, emotional, and psychological imperative. These poems, however, are far from traditional travel narratives. Instead, Blakely explores travel’s promise for escape, its ability to jolt one from the cruel simplicity of the known and the inherited cruelties of the home. Blakely both invokes and evokes the spirit of Charles Baudelaire, “skimming a secondhand Baudelaire” through lunch in New Orleans’s French Quarter (echoing Baudelaire’s own Latin Quarter) and also echoing Baudelaire’s perception of this life as “a hospital where every patient is possessed with the desire to change beds” and the soul cries out to travel “'No matter where! No matter where! As long as it's out of the world!’”

The collection is divided into five sections, each of which explore another aspect of the brutality of the ordinary and the necessity of travel. The poems in the first section, “Exiles and Returns,” speak of the terror which prompts us to run, the terror built of histories national, cultural, and personal. Blakely begins with a cinematic memory which her readers will certainly share: the shower scene in Psycho. In “Bad Blood,” Blakely writes of how this portrayal of one woman’s terror, “when death, / That black-winged angel, / Appears without warning, without any time for prayers, rescues,” brings us to terrors of our own even in moments we trust for comfort, such as the shower, where we trust “water like a lover to soothe, to cleanse of the grit // And smudge of ill-spent pasts, to give us a new start.” The poem melds the speaker’s experience with Marion Crane’s experience, ending on a prayer – “love me, treasure my body, don’t ever let me die” – a plea to be singled out in times of terror and reminding the reader that it is terror which defines us as human: we will all die.

Blakely then moves on to “Family Battles,” one of the book’s six sequences. In these modified sonnets, Blakely reminds us that horror is not limited to the horror film, but is perhaps most present in what is most familiar to us: our homes and our families. There is, for instance, her uncle Eddie, who “[s]pent most months at a VA hospital / Thorazined and crying in the chapel / For his buddies.” For Eddie, the war didn’t stop with the war, but lived on in his every action, even when, during Christmas lunch, he “winks at me and twirls the carving knife.” The sequence suggests that tragedy has the potential to transform, as in Temple Drake’s case, the Faulknerian “belle / Turned whore, she’s transformed by loss and contrition / When her child dies.” At the same time, Blakely hints that this transformation isn’t complete, or else isn’t perceived as complete. Even sexuality becomes a threat, as a priest jokes with the narrator as a child, “his chilblained right hand stretched / Toward my bent shag,” that “‘hairdressers call / On Mary as. . . . their patron slut . . . er, saint.’” Through this sequence, it becomes clear that there exists little difference between a war abroad and a war in a home; though bloodshed may be scarce, the terror is the same.

In the next sequence, “The Last Violet,” Mary Jane Kelly confirms that sexuality is inextricably linked with violence. Kelly, an Irish prostitute who was Jack the Ripper’s final victim, speaks of how poverty brought her to her occupation: she was, at first, “glad to scrub / A convent’s floors for porridge and a cot, / But who’d call these fair wages?” Though her profession may consist of sleeping “days after twisting the sheets / With proper husbands in derbies like yours,” she is able to “keep a lady’s ways: / This basin, my bottle of French perfume / And that small one of brandy.” Kelly is therefore able to make a home of the sort that is expected, if not respected; this home is, however, dark and dangerous, the place where “jealous wenches nicknamed” her “Black Mary.” She finds acceptance only in sex, in men “[w]ho go home late to their wives, long asleep, / Milk-faced and tight-kneed, dreaming of the Queen,” and is punished even by those who are meant to show mercy, as a priest hears her Hail Mary and “looked up from his prayers / Like I’d raved curses; he startled and made / The cross’s sign with his smudged, crookéd fingers.” There is no comfort, then, in the familiar, even in religion, as “we’re doomed to certain things by God.”

This idea runs through the rest of the poems, spurring the speaker to run from place to place, from escape to escape. In “Memphis Blues,” Blakely describes this city of great violence and glorious music, where she attempts escape within “the fallen raptures of this murderous world.” Even in travel, even in sex, there is no escape; in “On the Border,” Blakely describes sex as bloody and painful – “Delilah never warned me / Just how much this hurt / Or just how quickly I’d flee that boy” – but as necessary for love, which is itself bloody and painful, existing “to cross borders, slip into other bodies / With the same sweet ease / That we slip into sun-warmed grass or a river’s muddy flow” and, at the same time, as wire which “stings / And rips our flesh, wire saying Do Not Enter, saying Go Back.”

In the second section, “Blood Oranges,” Blakely skips from city to city, seeking difference and similarity, wondering, upon thinking of Lorca and Capote, “What do they share, and I with them, beyond / A language of desire and shame, of homes / Escaped then mourned?” The section begins with another sequence of modified sonnets, this one taking the way we travel, without choice through time and with choice through space, as its subject. Most of the poems take Manhattan as their subject, focusing on how that closely-packed life is fraught with emergency. However, it isn’t just the close proximity of city living which is the problem; the problem is, instead, any close relationship, which, contrary to what we’re taught to believe, is dangerous and brutal. In the third sonnet, “Houston Street Grille,” Blakely celebrates brevity in human relationships as she bids farewell to a lover, wondering “[w]hy do these encounters possess such allure / When short, their farewells always chaste, like this? / He’ll marry soon — I’ll miss him, more or less.” In “Travel Permission,” Blakely speaks of her female students and of women in general, who are “raised to be fulfilled with love, with friends.” But such teachings are traps, and dangerous ones, at that: in the Soho Guggenheim, Blakely speaks of deKooning’s famous women, “bent and fractured,” “scribbled with black, carmine, / Streaked cobalt and deep murky ochres, mirrors – of what?” The answer is, of course, all of us, and all of us women in particular. “Photography Wing” speaks of the pain of separation, even when return is promised, as “[w]hen my parents drove off to dinners, furred / And tuxedoed; I tantrummed, held my breath / Until my blood-congested cheeks turned scarlet.” Her parents return; it was “[a] false alarm” – though most alarms are not false, especially those regarding the home, which continues its treacherous lessons. In “Another Saturday Night,” Blakely describes how we are all born into a mess of a family, and how we use our own families and friendships merely as a method for repeated the trauma we’ve experienced, the harms that others have caused us:

But what terror freights our early steps from home,

From families we’re born to, none untroubled,

And toward these larger ones we make, messy

As the first with love and loss, our fumbled histories.

The final poem of this section, “Blood Oranges,” continues and alters this theme by presenting travel as a way to escape our homes and harms. The speaker takes the physical steps that led others – St. Teresa of Ávila and Federico García Lorca – to spiritual revelation, though each revelation leads her nowhere but home: “I want dreams / Of angels too, their wings hymning escape / From travel-smutted flesh. . . .as Southern suns / Force dogwoods’ buds to cruciforms.” “God is in the details, / Teresa said,” but for the speaker, the details swirl back to home and to a place she cannot equate with God, just with “legacies / Of shuttered rooms and Easter dresses stiff / With starch, the mingled smells of sour milk / And talc.” These ideas carry into the next section, “Following Signs,” and particularly the first sequence, “Home Thoughts from Abroad,” in which home and not-home combine with dizzying and disorienting effect. The speaker’s mother travels abroad with her to England; her presence reminds the speaker of home, and how happiness and unhappiness are inextricably linked: “‘I hate babies—they mess up your nice things,’ / My mother shrieks, my brother spitting up / On her bed’s counterpane, hand-tatted lace.” Even her mother’s marriage, performed against the family’s idea of “marriage for bloodlines, not happiness,” “turned bitter.” Blakely suggests that this is a situation intrinsic to the human heart itself, which longs both for what will heal it and what will hurt it, as in Larkin’s “poems that comprehend the heart, / How it craves love, also deprivation.” Perhaps nothing better represents this state than a woman’s state in marriage. Late in the sequence, Blakely moves to compare personal memories to cultural memories of women in domesticity: her mother to Sylvia Plath, herself to Vivienne Eliot. In the case of Plath and her mother, no matter how deeply domesticity is desired, it ends in tragedy:

Both houses white, both haunted by Furies

Who took their revenge as good women do,

Not with guns or knives but black depression,

One’s hair falling lankly from an oven door

As hissing gas choked our her eulogy;

The other crying in bed through whole seasons,

Wearing the same nightgown as summer air

Sharpens into fall. . . .

Through these women, the speaker learns how quickly the home becomes a trap; through Vivienne Eliot’s “bloody rags, / Head-blurring pills quacks said would stanch the flow / That continued red for weeks,” she learns how women are helpless to their own situations, how the only real solution is isolation: “At sixteen I knew what I wanted: / To be Prufrock, remote from those women, / Pliant and perfumed. . . . / To write poems as singing as Eliot’s dry bones.” Love, the speaker reflects during evensong at Westminster Abbey, is not the grand exercise proclaimed by church hymns, but damage: “God, what forms can / Love take except the smudged, the failed, the human?”

Blakely continues her meditation on the divine and human aspects of love in “Church of Jesus with Signs Following,” a sequence of poems dissecting a murder trial in her home state of Alabama in which a preacher attempted to murder his wife by forcing her hand into the cage holding his snake-handling church’s serpents. In this sequence, the holy and the dangerous are inseparable, signs of grace become “hot-fanged offerings,” and to have a family means that one is “made ripe for grief.” This is a situation inherent in Christianity, in Paul’s warning that one should not marry but that one had “Better marry than burn,” and in Christ’s command for all to “Turn the other cheek,” advice which necessarily extends to dangerous domestic situations. As Christians – and as human beings in general – we are therefore set up for a fall, or “backsliding,” as Blakely puts it, which is “serious stuff in Alabama, / But isn’t that why I return?” By the end of the sequence, Blakely’s speaker has traveled away from and back to home, now seeking salvation there, “wanting hands / To be laid on me, still following signs.”

Blakely’s quest for redemption and revelation at home continues in part five, “Home Movies,” a stunningly well-wrought and beautifully executed sequence of poems in which the speaker is forced to question both herself and her desire for escape. Though home is “a Dantescan pit” which “glitters into view,” it is also the locus of a history she inherits and shares, a history she must in some way accept even if she does not want it. Her parents greet her with the “surprise gift of home movies,” which begin with the burning of a foundry, “O dying town of Bethlehem Steel,” an event which takes her grandfather’s job and her great aunt’s will to live. Just as she did not ask for her history -- “Who gets to wish-list anyone as parent or child?” -- so did they not ask for this event. This triggers the speaker’s realization that examining one’s own history is, in the end, an exercise which ends only in more confusion. As in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup, tight focus and close examination lead only to dissolution, to questions, as Thomas’ photograph itself, which shows “a woman’s frightened face—there— / Then dissolve[s] to grain? Or is the body, / And the gun, a trick of light?”

The ultimate questions of our lives, therefore, have no answers other than uncertainty, dissolution. Travel, distraction, movement: all are redemptive because they involve escape, transport rather than catharsis, which, Blakely argues, is as useless as questioning one’s past. In art and in travel, in cinema scenes and in the footsteps of those who stepped before us, we are “[n]ot purged by transported!” – we are able to become. The poem ends with a series of sonnets for Tina Turner, that great icon of revelation, redemption, and transformation, who, through travels away from and back to the home, through reinvention and liberation, learns that the only real truth is that “We build ourselves, and love ain’t everything.”

Reviewed by Emma Bolden.

Poets’ Quarterly | January 2010.