Issue 4 - Winter 2011 Reviews Arranging the Blaze Beasts and Violins Crazy Jane Eating Fruit Out of Season Five Kingdoms Hard Rain Heathen Little Oceans Multiverse Open Slowly Psyche's Weathers Silent Music Something Must Happen The Apocalypse Tapestries The Darkened Temple The Kingdom of Possibilities The Tyranny of Milk This Pagan Heaven Woman on a Shaky Bridge You Know Who You Are Interviews

|

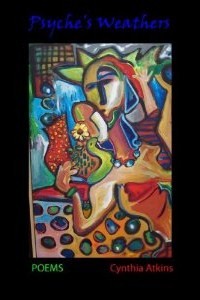

Psyche’s Weathers is a savvy testament to the presence of personal significance and communal sacredness in the most mundane aspects of our world. Cynthia Atkins’ debut collection investigates the deeper levels of the psyche as revealed in backyard nature and, simply, what’s around the house. It is precisely the familiarity of the images and settings in these poems that lay the groundwork for Atkins’ powerful insights and well-positioned departures from the familiar into the arena of the often shocking. This dynamic does not, however, come off as a juxtaposition. Rather, it reveals the inherently potent nature of the mundane. See, for example, what Atkins does with worn-out jeans in the poem “Dirt Poor”:

The delicately placed comma acts as a discreet nod to the idea that worn-out jeans are too inconsequential to mention in a poem or any dialogue about the dire consequences of Hurricane Katrina. However, the sheepishness of the nod is negated by the fact that the speaker does, after all, mention it, establishing that the jeans are indeed signifiers critical to the poem. They are the visual proof and pinching discomfort of poverty, and they signify more than simply a single pair of jeans, but the kind of clothing “rife” in post-Katrina New Orleans. Another barely perceptible part of the poem’s technical scaffolding is the line break after “worth,” which elevates the thought from a mere mundane aside. The pause infuses time for reflection, a move which in itself confirms that it is a detail worthy of such reflection. The speaker, one of the “dirt poor,” shows a high level of self-awareness in saying “that wasn’t worth mentioning,” by showing an ability to think outside the world of what she says and consider how it sounds to an outside observer, in this case, the reader. This level of self-awareness in the voice of the speaker lends power to poems throughout the collection, giving the reader not only the small details, but also the larger picture that contextualizes them. In so doing, we are shown their meaning in the world beyond the speaker’s: indeed, in our very own. For example, “Birthday Poem” is a sustained reflection on the dying moment of a friend, where the speaker pays close attention to the mundane items and events that may have accompanied that moment:

In less than a dozen short lines, Atkins shows exactly why such small details are worth mentioning. Because the exact details aren’t known, she provides them for her friend. The “contrail of words” invokes a jet painting white lines across the sky without her description ever departing from the shower stall, while in the next room, “[m]aybe Coltrane” was playing “as the cat knocked/a pen off [his] desk,” while in the street outside, “[s]omeone honked at traffic,” and even further away, across town or across the country “[a] push-broom washed across/a diner floor.” The speaker’s vision of the moment of her friend’s death, the most significant moment of his life, telescopes out to the mundane details of that very same moment as it passed through different places. The fact that the lines are short and the sentences grow grammatically simpler only adds to the presentation of the events as very small. And right in the middle of this sequence, the speaker slips in “a ripple skimmed the world.” These perfectly chosen words create an abstract image not at all out of place in the middle of mundane events because it describes them: like the ripple, they are barely perceptible movements that hardly touch the world. But this slender line also describes a ripple effect: a series of events touched off by a single action. However small the original action is, the effect is of potentially tremendous consequence. The Coltrane, the cat, the car horn, the death of a man in the shower—that all these can be contained in the same moment gives us pause to think about the larger world every time the furnace clicks on downstairs or the dog barks in the yard next door, and, amazingly, gives us this pause in real time—as we are reading the very poem itself. Another facet of the apparent mundaneness of every day life that Atkins explores throughout the collection is the trail of painful events underpinning the mundane ones. In a manner almost reminiscent of David Lynch’s 1986 cult film Blue Velvet, Atkins buries frightening past events in visual details that depict a life lived according to the cultural norm. For example, in “Weird Sisters,” the quote from Macbeth that serves as an epigraph tips us off that all may not be as white-picket-fence-like as it seems: “When shall we three meet again?/In thunder, lightening or in rain?” is immediately followed by an image of a typical family in the 1960s, the speaker and her sisters in “ponytails, pedal-pushers, and mid-riffs,” and their mother “in gloves, seamed stockings, and a Jackie-O hat.” As the poem progresses, their typical teenager activities turn witchlike, the details delving into the frighten underpinnings of the seemingly normal:

The speaker, in a matter-of-fact tone, reveals that psychological damage, physical pain, and terror are all part of the biology of her family, the very flesh and blood of her brother. Many of the poems in the collection pick up on strands of thought from the poems that come before and build their complexity; the poem that directly follows “Weird Sisters” is no exception. “Here’s One for the Band” probes the effect of the secret wounds revealed in “Weird Sisters,” as we see in the line “I burned the kitchen/candles all night long, in my paper-thin nightgown.” The “paper-thin nightgown,” is weighted by being the longest line in the poem and by the pause created by the comma, emphasizing that her nightgown is itself flammable. The speaker is playing with fire here, in more ways than one, blurring the lines of intention with prosody: the line break after “kitchen,” the comma, the line’s length, and the line’s staccato ending collectively lead the reader to question if she is burning the kitchen, the candles, or—herself. There is no word or tone in the this line to indicate to the reader that the speaker feels anything out of the ordinary took place in the kitchen that night. The calm, conversational tone which the speaker uses to deliver such heavily weighted lines brings into question what, exactly, falls into the categories of “normal” or “natural.” In “To Say Aloud,” the speaker casually comments that

She is nonplussed by the strange weather, and does not see it as unnatural. Strange weather, strange doings in the kitchen at night. . . all this is in the natural order of things. She accepts things as they are while still exploring our desire to make our mental weather more temperate:

Neither mental nor meteorological temperatures have reliable control buttons, and the need to come to terms with that involves a longing to connect to “something sacred.” This longing threads its way throughout other poems in the book, where it is fully realized in the most common of places. “At the Mercy of . . . .” opens with one such place:

The “[a]lmanac/of sunrise/sunset” harkens back to the very first poem in the book, “January’s Calendars,” which details how the speaker’s wall calendar is crammed with her family’s daily activities. The Almanac passage refers as much to this mundane measurement of sunrise/sunset (PTO meetings, school bus schedule, etc.) as it does to the inspirational red glow of the half-lit horizon at these times of day. In fact, the whole collection works toward an intricate dovetailing of the sacred and the quotidian into one cohesive whole truth. The poem, “God’s Watermark,” reveals part of this truth toward the end of the book. In this poem, the speaker relates a conversation she has with her young son about God:

She goes on to say:

By this point in the book, the speaker makes no pretence at saying “that wasn’t worth/mentioning.” Every detail of her son’s drawing held to the refrigerator by a magnet is worth mentioning. The magnet itself, worth mentioning. And here she tells why: because God is in the small, seemingly mundane aspects of our lives. This point is further emphasized by the clipped lines and abrupt enjambment: “God is in/the refrigerator magnet holding/his smudged drawing up.” The child’s drawing becomes a picture of our own world, filled with simple things and a Crayola innocence that endures, despite what secrets lie buried beneath. Reviewed by Christina Cook. |