Issue 4 - Winter 2011 Reviews Arranging the Blaze Beasts and Violins Crazy Jane Eating Fruit Out of Season Five Kingdoms Hard Rain Heathen Little Oceans Multiverse Open Slowly Psyche's Weathers Silent Music Something Must Happen The Apocalypse Tapestries The Darkened Temple The Kingdom of Possibilities The Tyranny of Milk This Pagan Heaven Woman on a Shaky Bridge You Know Who You Are Interviews

|

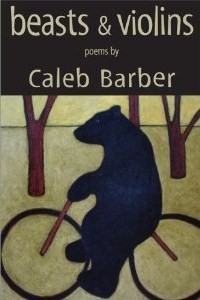

Despite the whimsically dark cover of a bear riding a bicycle and the curious title, Beasts & Violins, Caleb Barber wastes no time in letting the reader know that he is a serious poet. The first offering in his debut collection “The False Twin” begins with an epigram from a dead man poem by Marvin Bell “The dead man waits with the bear in its cave…”. ‘This works as an appropriate introduction to a difficult topic—the delivery of a still-born twin. Barber uses language, rhythm and image to pull the reader in and out of the action making us both spectator and participant in this birth. This heightens the experience of the poem, putting the reader in the narrator’s space, making us the living twin. Barber begins “The False Twin” in first person: “When I was born, the delivery room was still/for the baby being birthed dead.” Then he shifts to a third person perspective in the same stanza: “The doctors had been aware of it for weeks/and so had its parents…”. We are outside of the action without being lost and without being able to turn away from what Barber is showing us. He holds us with his words; we are voyeurs to others’ pain. This is the skill with which Barber tackles every poem; he uses the same keen eye, identical sharp language. He turns his talents to nature in “False Eulogy for the Stillaguamish River on the Day of Gerald Ford’s Funeral 1/02/07”. In this piece, Barber reflects on the changes of a once mighty river on the day a once mighty man is laid to rest. “False Eulogy” is both narrative and contemplative, giving us a brief history of the river while examining man’s relationship to it. The imagery and language combine here to make memorable lines: [the river] was not a strong brown god, but gray and capacious. Rather than Hindu ashes, the Stillaguamish would have born the distended corpses of raccoons and deer, each twitching with parasites, like demonic ice cubes, on their long float.

Rabbits have no tail and a river has no ass. Rivers only have headwaters and mouth. We can almost see the river, smell it, and wonder ourselves what lies beneath it. If we go a little deeper maybe this will lead us to question what is beneath all greatness, what twitches unseen. “False Eulogy” is a poem that reaches further than its intended topic. As Barber says in its closing lines: “…a river can never flood/A river can only reclaim.” Like the Stillaguamish, this poem does not overreach but helps us reclaim a connection to nature. Not all of the works in Beasts are dark. Barber has a sly humor that can only come from a critical and observant mind. “My Boss is a Jewish Carpenter” ruminates on a bumper sticker that bears those words and is attached to a septic truck full of “bourgeois shit”. The narrator’s voice in “They Couldn’t Even Kill Their Television” seduces us with humor but turns serious when we realize that the narrator is rejecting marriage for fear of becoming his girlfriend’s “…poor stepfather…his teeth gone feral, and his eyes turned laser blue.” Barber works in an aerospace machine shop therefore blue collar life informs Beasts & Violins. This gives his work a solid foundation from which to explore other topics and an authenticity that cannot be ignored. He is also a traveler and that too influences his work. When he is in Bisbee, Arizona we see Bisbee; we witness the “alien lightning...collected like pulsating night clouds at the summit of the Mule Mountains…” that he describes in “The Southwestern State”. We also feel his lack of connection to Bisbee and Barber captures this disconnect with the layout of the poem: But I wish I were authority on this weather. How could it be so silent and so near --glowing with ocotillo and rock.

What produces this? This ghost frequency I’d discovered strictly before midnight in the summer. With my sorrow and inability to write So well concealed.

We think between the pauses, anticipate the next word and, although we can see the word, we are surprised by how much weight they gain when they stand alone as demonstrated. One of the strengths of this collection is Barber’s handling of relationships—especially those that do not work out as expected. In the title piece the narrator discovers a notebook left by a former girlfriend. Inside it had lists. Lists of bands, places, problems ---with notes detailing why my ex-girlfriend was unhappy. My name appeared on most pages. It was hers, left on the bookshelf for over one year. She always kept lists, as if her life could be categorized into columns of good and bad, written repeatedly like an incantation, banishment spell or scale. In that stanza, Barber sums up the relationship, we know why it didn’t work out and like him we are ready to move on. When this poet moves on he does it with certainty. …So I ripped out her pages, stuck them in the winter fire. The flames made me happy. Filled me up, like I was drunk in a train car lounge, and every time I checked my wallet, I’d find another twenty.

…I’d jump off my stool and dance right there on the train. The snow would be too high for the wolves to give chase. Their eyes would cut tree limbs as they raised their heads to howl. This collection punches harder than its weight. The working-class perspective Barber brings is refreshing, yet honest and unflinching. In “Teaching the Beasts” we see the inside of the machine shop with its “CAD machine forever on its rails” and its bay doors and stacks of pallets with an old dog chasing young rabbits over a barren landscape. “From the Employee Kitchen” we see and smell the “microwaveable ham and cheese omelets/on top of bumpy sausage patties/between cinnamon-raisin bagel slices.” We know there is a hierarchy to food and that “the color/of your collar depended on the hours/of your shift.” This is the world where people take a shower after work and not before; those who literally grease the engine that runs the machine, and like those internal parts, we refuse to see them unless they are broken. Barber makes us see them—whole and broken-- he makes us understand this way of life, and he honors the hard-working. With Beasts & Violins, Barber grabs the reader’s attention from the first line and does not let go even after we’ve read the last poem and closed the book. Reviewed by FeLicia Elam. |