Issue 4 - Winter 2011 Reviews Arranging the Blaze Beasts and Violins Crazy Jane Eating Fruit Out of Season Five Kingdoms Hard Rain Heathen Little Oceans Multiverse Open Slowly Psyche's Weathers Silent Music Something Must Happen The Apocalypse Tapestries The Darkened Temple The Kingdom of Possibilities The Tyranny of Milk This Pagan Heaven Woman on a Shaky Bridge You Know Who You Are Interviews

|

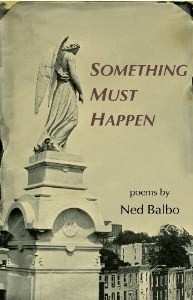

Although the line “Something must happen; that’s the source/of all suspense” refers to a movie set in Balbo’s poem “Actors Talking While They Drive,” the sentiment provides a lens through which the reader is invited to read his chapbook as a whole. The poems in this collection are, by turn, historical and personal, weaving together the suspense of impending things on the smallest to the largest scale. The two pillars of the book together take up twelve of the twenty-eight pages: “Times Square Postcards” details the picture history of New York in the first half of the 20th century and “The Woods” details a two-year span in the personal history of the speaker. Both these poems have subtitles featuring the exact dates in which the events described took place, as do other poems throughout the book, giving the collection a generalized feel of a non-chronological timeline of events which either definitively or possibly happened. “The Woods” explores the weight of potentiality that tips the scales towards the inevitable as underscored by the book’s title. The poem is strongly reminiscent of Wordsworth’s The Prelude—a connection I am rarely able to make when reading contemporary poetry. The long lines, dense stanzas, and choice to use no jarring enjambments, in addition to the formal diction and melancholy tone, make me want to dig out my old copy of Wordsworth. For example:

As with Wordsworth’s choice to title his coming-of-age poem The Prelude, so too does “The Woods” depict a sense of something impending, and Balbo conveys this on two intertwined levels. First, the poem opens and closes with images of the woods slowly moving in to swallow his friend’s house and the things that happened there. In the first lines, “The woods closed in—who knew how long they grew,/planted or wild, around your rented house,” the “rented house” emphasizes not only the transitory status of his friend’s family, but the similar impermanence of human nature. This trope surfaces in the last lines, as well:

Secondly, events unfold slowly and are left unresolved, in a state of permanent unfolding. Over the course of 92 lines, the speaker gives us these snippets: “your brother Johnny, not yet drafted”; “One day, I met your brother’s hippie girlfriend”; “But the worst/was yet to come” (because Balbo does not often use enjambment to produce an effect, when he does, the result is stunning); “Johnny, I later heard,/was sent to Vietnam like many more,/but made it back—on furlough or for good?—/home to his hippie bride.” That question mark, coming at the end of the piecemeal unfolding of what possibly came to pass, freezes Johnny, particularly, and his generation, more generally, in a state of permanent suspense, where something is always about to happen. Going forwards in time, but backwards to the first poem in the book, “Snow in Baghdad” also uses war as a haunting backdrop to moments made remarkable by something else, in this case, snowfall in Iraq for the first time in 100 years:

The soldiers’ peacetime presence is a nod to their state of being continually on-guard. Under these conditions, surprise is impossible, and Balbo expertly uses the sonnet’s structure to emphasize this. Although a sonnet’s turn typically adds a new thought to the poem, inviting the reader to see the previous twelve lines in a way which brings resolution of some sort, here the turn provides no surprise, and no resolution. After twelve lines of visual and auditory imagery describing the falling snow, the closing couplet reveals that “one old resident exclaims in wonder,/’In all my life I’ve never seen such rain.’” It is not surprising to hear the Baghdad native call snow “rain” because the first line of the poem has already revealed this: “The snow so rare that people call it ‘rain.’” In any other poet’s world, this would have deflated the punch line, but surprise does not exist in Balbo’s because his world is defined by a constant state of expecting things to happen. In his world, there is no punch line, and the sonnet’s form itself is used to express this. The collection is rife with references to wartime, but historical events and people unrelated to war also play out their own eventualities in the poems. The last poem in the book, “For the Next-to-Last Survivor,” is addressed to the second-to-last person alive who survived the sinking of the Titanic. This sonnet functions as a historical flashback from the 2008 snowfall in the fatally dangerous city of Baghdad to the tragic memories of Barbara West Dainton, who died the year before:

Death came to the soldiers in Vietnam and will come like snow to the soldiers in Baghdad, whether in the heat of the tragedy they witness, or many years after the fact as it came to Barbara Dainton. It will come, and will come to us all differently. Death is one of many things that have happened in the past, and one of many things that will happen in the future. Indeed, it is something that must happen, and Ned Balbo’s chapbook is a throughly engaging exploration of what such a cycle of suspense brings to bear on the course of its instigator, time itself. Reviewed by Christina Cook. |