Issue 4 - Winter 2011 Reviews Arranging the Blaze Beasts and Violins Crazy Jane Eating Fruit Out of Season Five Kingdoms Hard Rain Heathen Little Oceans Multiverse Open Slowly Psyche's Weathers Silent Music Something Must Happen The Apocalypse Tapestries The Darkened Temple The Kingdom of Possibilities The Tyranny of Milk This Pagan Heaven Woman on a Shaky Bridge You Know Who You Are Interviews

|

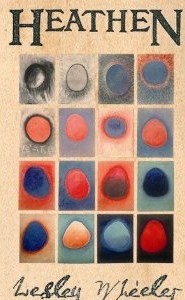

Okay, first, full disclosure – Lesley Wheeler and I collaborated on the editing of an anthology of poems that was published back in 2008. Rosemary Starace, whose “16 Circles” is the cover art for Heathen, was also a co-editor of that anthology. I live on a different continent than the two of those women but I loved working with them both then. And now, I love the work of them both. But to the poetry… The title, Heathen, is a brave one to put out into our world in which the term is viewed askance at best and, pejoratively, as threat or insult at worst. Also, often misunderstood, ‘heathen’ does not necessarily mean no belief, no faith in anything at all. If pressed for a word, I’d describe myself as heathen and I approached this poetry with real interest as to the subject matter. The prefatory poem, in its way, introduces the mystery of (pro)creation sans religion…

The rest of the poetry is collected into five sections and the works of the first are coloured, delicately, in fleeting shades of pain – the growing pains of girl to womanhood. Wheeler uses a variety of verse forms and I’m particularly admiring of her harnessings of sound as, for example, in this bit of a terza rima which swirls ‘mages in a pickup truck’, ‘arrogant sheep’ and a ‘quorum of priestesses and hags’ into a

or when, during…

Yet before the section ends, the narrator returns again to the thread of heathenism in no uncertain terms:

Becoming parent must be the time when a woman feels, most, her vulnerability and when her assurance is most seriously undermined. It’s a time when religious faith could be so very comforting. These poems in the third section are filled with the defenselessness of young children, awareness of the dangers that beset them, and of a parent’s essential helplessness to do very much at all by way of protection.

The title of the above poem is, “Heathen” and the poems in the following section of the book are grouped under the title, Resisting Conversion. They speak of chaos and uncertainty and of unravellings as in “Defending Our Way of Life” where…

And again, in the last section of poems entitled How the World Talks Back the narrator finds, in a poem on the subject of supernumerary nipples, that

But in the end, the book’s narrator does triumph on her very lonely chosen path and in another subtly crafted, subtly argued terza rima:

Reviewed by Moira Richards. |