Issue 4 - Winter 2011 Reviews Arranging the Blaze Beasts and Violins Crazy Jane Eating Fruit Out of Season Five Kingdoms Hard Rain Heathen Little Oceans Multiverse Open Slowly Psyche's Weathers Silent Music Something Must Happen The Apocalypse Tapestries The Darkened Temple The Kingdom of Possibilities The Tyranny of Milk This Pagan Heaven Woman on a Shaky Bridge You Know Who You Are Interviews

|

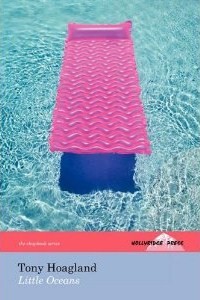

Poetry doesn’t need to swim exclusively in the deep. Good poetry must also examine the surfaces, with their foams and frolics. And in Tony Hoagland’s Little Oceans there’s a humor that rides the waves. It swells with a good smattering of insight, along with cynicism, sarcasm, and irony. Hoagland simultaneously makes you laugh and makes you dive right into the profoundest of seas, even if you are only a “guy on a rowing machine / who is stroking across a cardiovascular ocean.” So, Hoagland’s poetry isn’t doggerel; and his insights never cliché, although he’s often on the brink. No. Hoagland entertains in a delightful intimate way like a deep-thinking best man at a wedding, as he expresses what you’ve known and never said. And also like a best man, he makes you squirm (and relishes the discomfort). Whatever he does to get to you, you dog-ear page after page, because there’s always something worth remembering. You remember, first, the beautiful electric-pink air mattress against the aqua-marine water on the cover of Little Oceans, and you overlook the typos and the punctuation errors of the book because they are merely writ in water. Fluids, fluids everywhere, and lots of drops to drink. The little oceans are gigantic at times, and truly little at others. Take for example, how out of a machine emerges—rather, is spat—a soft drink “where something dark and sweet is sparkling.” There is a Homeric sea in Hoagland’s every soda can. The title poem itself contains iced tea and sherry—and not much at that, one inch in each glass—a little ocean, indeed. And the poet—“some kind of little Magellan” himself—is “dying of thirst,” “while trying / to catch a glimpse of life’s interior.” He is the insignificant explorer who discovers magnitudes. He is the only person in the world, and he is the billions, as he affirms in this passage from “Jazz”:

On the edge of cliché, the poet admits “. . . when I’m in one of these moods, I find it / a little too easy to believe the trees are suffering.” See? He is the billions, for who has not at one time or another experienced sadness behind the wheel? Like oil, a melancholy flows freely among Hoagland’s lines. To read “Texaco,” a poem obviously written before the BP self-inflicted tragedy in the Gulf of Mexico, is to look in the mirror at a society dependent on gasoline. The poet fills his tank

“This moment” is here for Hoagland, and it is filled with familiar signs and today’s commercial symbols. But it is also not here yet. Hoagland wants it like that, always maintaining a delicate suspension between the little oceans and the skies above them, between the tear and the laugh, between thirst and the quaff. Reviewed by Anne Harding Woodworth. |