Issue 4 - Winter 2011 Reviews Arranging the Blaze Beasts and Violins Crazy Jane Eating Fruit Out of Season Five Kingdoms Hard Rain Heathen Little Oceans Multiverse Open Slowly Psyche's Weathers Silent Music Something Must Happen The Apocalypse Tapestries The Darkened Temple The Kingdom of Possibilities The Tyranny of Milk This Pagan Heaven Woman on a Shaky Bridge You Know Who You Are Interviews

|

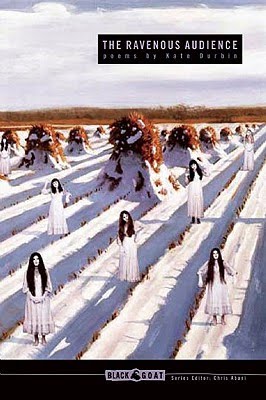

Jill Crammond Wickham: In a Delirious Hem interview, Arielle Greenberg defines the Gurlesque as “a new and widespread approach to femininity and feminism,” a granting of permission for women “to be unabashedly girly, to talk about things like ponies and sequins, while also trying to be fierce, carnal, funny, political, irreverent…all these things at once.” Your poetry seems to fit perfectly within this definition. How do you define Gurlesque, and do you consider yourself a Gurlesque poet? Kate Durbin: I think you are right, Jill, that some of my poetry fits within the description above, and some of my favorite poets are the gurlesque poets—people like Lara Glenum, Ariana Reines, and Danielle Pafunda. One of the definitions I’ve resonated with is one Lara Glenum gave in an interview with Ruan Klassnick. She said: “The Gurlesque describes female poets and artists who draw on burlesque performance, kitsch, and the female grotesque to perform femininity in a campy or overtly mocking way. Their work assaults the norms of acceptable female behavior by irreverently deploying gender stereotypes to subversive ends.” With this definition in mind, I certainly think some of my poems lend themselves well to a gurlesque read. For example, a poem in The Ravenous Audience called “Doll Disrobed,” which is a cannibalistic take on Plath’s “Lady Lazarus” (and an indictment of how women are read culturally, and particularly how women writers are read). That poem is a language striptease, a sinister burlesque, a campy fashion show, and it’s inappropriately funny, mocking and scathing. The aspect of my work that I think could be read through the gurlesque lens, too, is my costumes. However, for me to personally apply someone else’s description to my work feels suffocating, namely because I am trying to work out my individual aesthetic—to perform it—each time I sit down to write something, or make a costume. I am all for an evolving personal aesthetic philosophy, but that is something else. So for me, the above description is one way to read some of my poems and costumes—and an exciting read at that—but it’s certainly not all that’s going on in my work. What is it about the female experience that you would like readers to take away from your poetry? I am very interested in exploring in my writings the ways in which women internalize misogyny in our culture, the ways in which we are blind to our own self-victimization, the ways in which abjection can be both liberating and destructive. We must go down into the wound, like Ariana Reines writes in The Cow. I want my readers to go down into the wound with me. If we go together it will be easier than going alone. However, if we do this at some point we will no longer be victims. And I think some women want to stay victims, as it is easier to be a victim than to have power. I want power. Real power—the kind the witches had, or Joan of Arc. When they went to willingly to the stakes, rather than surrender their power. Real power has nothing to do with whether or not institutional sexism exists or not and it has absolutely nothing to do with what men do or think about women. Women’s power has nothing to do with men at all and that is why it is dangerous. Who are your greatest influences? Too many to say, so I’ll just list who comes to mind immediately. In terms of literature, in the beginning there was Sylvia Plath. She made me want to be a poet; everyone before that was a dead white English guy. Then, the Bible, Artaud, all the romance novels I read as a girl, the horror novels, the trashy teen magazines. Mina Loy is a strong current influence, also the Baroness von Elsa and Djuna Barnes, the modernists, but they are influences for my current project, Excess Exhibit, not for The Ravenous Audience. Caroline Bergvall influenced some of the latter poems in Excess Exhibit as well. Simone Weil and Clarice Lispector are two of the most important writers, ever, for me, and I re-read their works constantly. They are influencing my current novel project. I am working on a short chapbook right now that is very influenced by Jon Leon’s The Hot Tub, which is the only book of poetry I’ve ever read that felt truly contemporary to me, like a pop song. I am as influenced by fashion, contemporary art, and film, as I am by literature. A very few of my favorite film directors are Catherine Breillat, Lars Von Trier, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Takashi Miike, and all the French Extremists. I go to art shows almost every weekend in Los Angeles with my husband. I’m extremely influenced by the shock artists and the Dadaists, as well as anyone who has takes extreme measures to jolt the masses out of their collective coma, so I would consider self-immolators and Jesus Christ to be influences. The crucifix is the most powerful piece of shock art in the world. I often feel like a love child of the 70s/80s feminist performance artists (Karen Finely, et al.) and glam shock artists (Leigh Bowery, et al). You often make interesting leaps in thought in your work—a sort of stream of consciousness with a purpose. Do your poems generally spring forth fully formed? Not at all. It takes me ages to chase down my poems, with a few notable exceptions, such as “Gretel and the Witch,” which I wrote (cackling to myself) in one eight hour period. When I wrote that poem, I didn’t know that Gretel would eat her brother at the end, I just knew the poem would take a wrong turn somewhere, would end up being deranged and probably cannibalistic. So in that sense it was a stream-of-consciousness, I suppose, or at least, a poem channeled quite effortlessly from the cultural unconscious (our culture is quite cannibalistic, spiritually, sexually and otherwise). Also, my poem “23 Erotic Dreams of Sarah Palin” was written in about twenty minutes, which is insane. Especially since it’s many people’s favorite poem I’ve ever written. With that one, too, I was very much tapping into the cultural unconscious. I didn’t care personally about Sarah Palin, and hadn’t paid that much attention to her—which was probably why I was able to drudge up these various cultural beliefs about her, without having to filter those through my own political opinions. Which is also why that poem should piss off everyone, regardless of his or her political stance, because it deals with such a deeply entrenched cultural misogyny, something Palin really taps into because she is both a political and sexual figure, unlike, say, Hillary Clinton. However, I want to speak the leaps of thought you mentioned. No matter how much research or time goes into a poem (for example, I researched Marilyn Monroe and worked on her interview for six months), I never have a totally clear idea of how or where I want the poem to end up. That way, I can open myself up to tap into our cultural unconscious in a way that is very much like a medium channeling the dead. At some point I let go of my “ideas” or “concepts” of the poem or the woman in the poem or the form of the poem, which is a structure, an institution. Often that’s near the end of a piece that I “let go,” and then there is the apocalypse, the walls crumble, a truth is revealed in the rubble, before it is covered up again (and the institution is re-built, so yes, I realize the irony and impossibility here). This is crucial; otherwise writing poems cannot change me. This ties back to my losing my religious faith through writing this book. I am only interested, as an artist, in fire. I am not interested in re-affirming what I already believe about the world, nor am I interested in encasing my childhood behind glass so everyone can admire it and give me the attention and praise I never had as a girl. I am interested in immolation. I want to burn through poetry (both the experience of writing, and reading it). I want to rise from the ashes to become—not literarily, but literally—something beyond possible. And, eventually, one day I may not need poetry to do that; perhaps this won’t happen until I die and become something else, or perhaps it will happen before. I do not think the worst thing that could happen would be to quit making poems, if you don’t need them anymore. I want to be clear that I don’t believe in the immortality of poetry. I don’t see poems as sacred; I see them as a normal part of life, like fashion and fucking. When I was a girl I used to write in my books, I would add on endings to the chapters, or insert new dialogue. The text is not an object that is sacred; it is alive as a maggot is alive; it takes on new life for anyone it touches, and translation as an act is a beautiful example of how a poem can mutate depending on who is eating it, praying it, breathing it, fucking it, wearing it. Do you have a daily writing practice? I wish. I suffer from debilitating insomnia and an over-full schedule, so often I go weeks without writing, then work in giant spurts to make up for it. I used to feel guilty for not writing daily, but now I am trying to tap into the passion I felt as a child and young adult for writing. It wasn’t something I “had” to do, but something that was privately mine, a furtive passion like eating a secret stash of candy or reading sex articles in Seventeen magazine. Perhaps this will make me more productive, who knows? And, if it’s really that good, who cares? Do you ever get “stuck”? If so, how do you remedy it? Yes, I often get stuck. When I do I watch films, look at fashion online at Style.com (or get dressed up and do my makeup), go to art shows and readings in L.A., hang out with my writer and artist friends and feel inspired because they are so amazing, read poetry blogs like Exoskeleton & Frances Farmer is My Sister, listen to the radio show Bookworm with Michael Silverblatt because he is so passionate about books that it makes me want to write them, and of course, read. I actually only write surrounded by books and it helps tremendously. When I get stuck, I open one and read a few lines, and then I can usually go on. I don’t believe in forcing things, though. If it’s not coming, go have sex, go to a party, eat cake. On any given day, what might inspire you to write a poem? I’m generally not the sort of writer who writes from a different inspiration every day, though I am often inspired and collecting notes and images for future use. I have a folder on my computer desktop for images; I also keep tons of images in the folders for individual writing projects. With poetry, and my writing in general, I am more project-based, and tend to work on a project through to the end, with an evolving concept in mind—though I may work on several projects at once. When I was writing The Ravenous Audience, I had a list of topics for poems and I worked off of the list. The list was something like: Clara Bow silent film, Marilyn Monroe interview, Marilyn closet, Earhart’s final flight, Jesus/felt board poem, etc. Not everything on the list made it into a poem, and not all poems I wrote made it into the book. I do get ideas for projects often—often titles, and/or concepts, and I write those in my notebook, along with costume ideas and notes on books I’m reading and films I’m watching. Anything might inspire me—often it’s pop culture, but also “fine” art, film, history, the paranormal, mysticism, apocalypse, and of course, larger concerns of sex and death and God and art, all of which are really the only concerns. Right now I am writing a chapbook based on a costume I bought, so in this instance fashion inspired me. How do you edit? Intuitively and obsessively. I like editing. It’s like doing makeup—very relaxing, and I can spend hours putting lipstick on my poems. How involved are you in your local poetry scene? I’m becoming increasingly involved in the poetry scene, local and otherwise. I have done a ton of readings this past year, many on the “Spoken Word” circuit, which is bizarre because I write avant-garde poetry. I’m the only avant-garde poet I know who reads to these crowds, and it’s thanks to Rafael Alvarado who has always supported my work and who books the shows. It bothers me sometimes how classist the avant-garde poetry community can be—many avant writers only read to super educated people. As for the scene outside L.A., there are a lot of poets I really connect with who don’t live in Los Angeles, but whom I keep in touch with via email or their blogs. I also have some wonderful writer friends in L.A. There is a very cool community of writers in L.A., and some great presses and venues such as Les Figues, Semiotext(e), BLANC Press, the Poetic Research Bureau, etc. It’s important for me—because art is so important to me—to seek out and support artists of all stripes who are doing work I think is significant. I do this more as a patron, or a consumer, than as an artist. I’m hoping that one day I will make a lot of money on some trashy commercial fiction piece, and then I will provide for all the artists that I care about, especially the poets. Do you feel more inspired when working with peers, or are you more of a solitary poet? If you had asked me this question a year ago, I would have said I was a fiercely solitary artist, like Henry Darger. But now that I am working on a collaborative poetry project with the amazing poet Amaranth Borsuk, I would say that I am currently hugely inspired and challenged by doing collaborative work. Working with Amaranth has been a complete gift. We have learned to mind-meld, and to overcome insecurities, issues with control, etc., in order to work together in this marvelous way where we made something that would have been impossible for us to make on our own: a language cathedral. In addition to these mind-bending poems, Amaranth and I have created what you might call weeping statues/conjoined twins with language gems to go with the text; creatures who wear fabulous, bizarre costumes (the look we are working on now is called “Patriotic Gangster Marie Antoinette Mermaids”) and are physically conjoined by hats or bouffant wigs and facial expressions (in readings). Just posing for photos together and doing readings has been a physical challenge, a visceral exercise in learning to “become” with someone else, to shake up ones ego in the service of art. It’s sort of like the Chapman brothers melded nude statues, except with more positive post-human connotations. What projects are you currently working on? Excess Exhibit is the collaborative poetry book that I’m working on with Amaranth Borsuk, and it includes illustrations by visual artist Zach Kleyn. We wanted to write about overabundance–of sound, of self, of sense–and in doing so, an ecstatic crossbreed emerged, both prophetic and post-human. These are conjoined poems about glorious mutation, and the nature of collaboration itself. The poems, ornate and visceral, grow one into the next, recombining in ever more rapturous and kinky ways until the helix of language and image spins out of control. The poems toward the end of the book actually become post-poems in a sense, language spasms, poems beyond poems. The illustrations and text act as a flipbook when the reader thumbs through the book. You can view video of us recently reading from the collection at REDCAT here. I am also working on a chapbook, Kept Women, for Insert Press, as a part of their PARROT anthology. That’s the chapbook written after a costume; the subject matter is Hugh Hefner and his girlfriends. The third thing I am working on is a horror novel called The Husband. What books are on your nightstand/in your purse or backpack/in your hands? These are the books I’m reading or re-reading right now: The Gurlesque Anthology, Carl Jung’s Dreams and Reflections, Clarice Lispector’s Stream of Life, a Samuel Beckett anthology, several books on biology and reincarnation, Vanessa Place’s La Medusa, Bataille’s Visions of Excess, Elfriede Jelinke’s Women as Lovers, Roberto Bolano’s Distant Star, Stephen King’s It, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Rebecca Loudon’s Cadaver Dogs. What’s the best piece of writing advice you ever received? Chris Abani, my professor at UC Riverside and the person who eventually published my manuscript, told all his students to write about things that terrified them. He said without risk there is no art. His charge changed my entire method of art making, which is to say it changed my life. Also, Rainer Maria Rilke’s advice in Letters to a Young Poet: “Nobody can advise and help you, nobody. There is only one single means. Go inside yourself.” Interview by Jill Crammond Wickham. |